Empowering PSHE Leadership: Leading with DEI Principles

Written by Malarvilie Krishnasamy

Malarvilie is a seasoned leadership consultant, coach, and trainer with over 20 years of experience in education. As a former history teacher and senior leader, she passionately advocates for coaching as a catalyst for transforming school cultures. Malarvilie offers accredited courses, endorsed by The Institute of Leadership, which develop emotional intelligence and assertive leadership skills. Her reflective and supportive programmes enhance staff morale and well-being, promoting humanity in leadership. A vocal proponent of equity, diversity, and inclusion, she actively engages as an ally through speaking engagements, workshops, and amplifying the work of others. Malarvilie is also deeply committed to promoting Personal, Social, Health, and Economic (PSHE) education, recognising its pivotal role in nurturing well-rounded individuals.

I’m excited to tackle a topic that’s not just important but essential in education: leading PSHE with a DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) lens. As educators, we know that PSHE isn’t just about teaching facts; it’s about nurturing well-rounded individuals who are equipped to navigate the complexities of life. That’s why it’s crucial to infuse DEI principles into our PSHE curriculum, acknowledging and respecting the diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences of our students. Join me as we explore how embracing DEI principles can transform PSHE education and create a more inclusive learning environment for all.

In many cultures, discussions about puberty, relationships, and sexual education may not happen at home. This leaves young people to rely solely on their friends or inaccurate information from the internet. This highlights the importance of PSHE education as a reliable source of accurate information. By providing comprehensive and inclusive PSHE/RSE in schools, we can ensure that all young people have access to the correct information, regardless of their background or cultural context.

Moreover, fostering an inclusive environment in PSHE lessons creates a safe space where students feel comfortable discussing their experiences and asking questions. This helps break down barriers and ensures that every student feels valued and supported in their journey through puberty and relationships, not just in terms of biological changes but also emotional and social aspects.

But leading PSHE isn’t just about delivering lessons; it’s about cultivating a whole-school approach to well-being and inclusivity. This involves considering staff values and providing them with comprehensive training sessions to navigate sensitive topics effectively, ensuring alignment with the values of the school, the curriculum, and the 2010 Equality Act. Staff members, while bringing their own values, must understand and adhere to the principles outlined in the Act, which mandates the promotion of equality and diversity within educational settings.

Additionally, understanding local and national statistics regarding teenage health issues, such as drug use, alcohol misuse, underage sex, lack of condom use for teenagers, and teenage pregnancies, equips educators with evidence to emphasise the importance of PSHE education. By sharing this information and ensuring staff awareness of their duty as PSHE teachers within the British curriculum, we can empower them to confidently and effectively deliver PSHE education, thereby supporting the well-being of our students.

But PSHE leaders often get left out in the cold. Schools know PSHE is important, but they don’t always give leaders training to lead effectively.

The challenges faced by PSHE leaders extend beyond traditional teaching roles. Effective communication with staff, parents, and students is paramount, but the support in developing these skills often falls through the cracks. PSHE is a whole school subject. Unlike other subjects, it’s rare to have dedicated PSHE teachers, and leaders must coordinate a diverse group of educators, each with their primary subject expertise. This aspect is often underappreciated, with a mere 1 management point failing to reflect the intricacies of PSHE leadership.

Additionally, the unique pedagogy required for PSHE is often overlooked in training programs, preventing the ability to deliver PSHE effectively. It’s time to invest in the professional development of our PSHE leaders.

That’s where the Level 5 Inclusive and Progressive Leadership of PSHE Course comes in—a comprehensive solution to bridge these gaps. This course equips PSHE leaders with the skills, knowledge, and awareness needed to excel in their roles. From diplomacy and communication to the unique pedagogy of PSHE, this program addresses every facet of effective PSHE leadership.

Conclusion

Leading PSHE with a DEI lens is not just a responsibility; it’s a commitment to creating a safe, inclusive, and empowering learning environment for all students. By incorporating diversity, equity, and inclusion into our approach to PSHE, we ensure that every young person receives the support and education they need to navigate the challenges of puberty, relationships, and well-being.

Equipping staff with the necessary training and awareness of their duties under the 2010 Equality Act empowers them to deliver PSHE education effectively, promoting the health and well-being of our students. Let’s continue to champion a holistic approach to PSHE leadership, where every student feels valued, respected, and supported in their journey toward adulthood.

Click HERE to download your free PSHE DEI self-assessment!

Click HERE to download your free KS2 or KS3 Diverse Perspectives self-assessment!

Also for further resources have a look at the The Diverse Educators’ Inclusive RSHE Toolkit – Inclusive RSHE Toolkit | Diverse Educators We are collating a growing bank of resources to help you to review and develop how inclusive the RSHE provision is in your school.

So You’re the Coachee

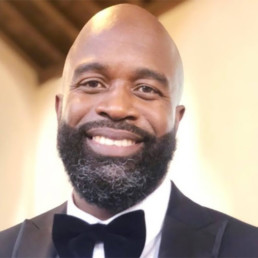

Written by Dwight Weir

Dwight is a Deputy Headteacher and Life Coach. He is also an inspector for British Schools Overseas. Dwight has a passion for coaching and leadership development.

Oftentimes we hear about the coach and the skills required to be an effective coach. Not much is said about the coachee – the other very important one in the relationship. The coachee, is a person who receives training from a coach. My learnings from various coaching experiences as a coachee have allowed me to craft certain skills and attitudes which I share as the skills or attitude needed by coachees.

- You answer your own questions. In answering your own questions, you are often engaged in a radical thinking process, examining your challenge and context and then finding the best way through the challenge. The thinking environment is a philosophy of communication developed by Kline (2009), which enables people to think for themselves and think better together. It is a simple, rigorous and radical set of processes. Coaches don’t answer your questions but provide you with the means to think through and find answers yourself.

- You take more risks – It is through risk taking that you know if your ideas will work. On the journey to success – radical decisions are made. You make these decisions as you know you’ll be able to reflect and discuss your thought process with the experienced other – the coach.

- You become more reflective – a great amount of the discussions with the coach is reflective. Researchers such as Muir and Beswick (2007) suggest that there are different levels of reflection that can take place, which move from descriptive to critical forms. It is the critical reflections that help us transform our practices.

- You must embrace quiet moments – embrace quiet moments as you think through your own hurdles. During the mentoring process these quiet moments are filled with answers by the mentor. Within the coaching relationship you don’t need answers you need a sounding board – the experienced other – the coach, to discuss your ideas. Here you find out for yourself. Notice ‘find out’ not told about.

- You become open to criticism – great coaches are frank and open. In coaching relationships you are told the brutal truth about your observed movements, dialogues, expressions and attitude. During your intake session a good coach will ask you how you’d like to be challenged or not. Does it make sense you start this journey, not wanting to hear the truth? Feedback is a gift. You can return the gift. But on these occasions, you keep the gift, as in true coaching relationships trust is the base from which change is realised.

A lot can be gained throughout coaching journeys and relationships. What is more and more apparent is, coaches don’t give answers but feed with questions which enable meaningful thought and self-discovered answers to your challenges. This is a skill only the experienced other could exhibit flawlessly and empower the coachee to unravel options and find answers. I describe this process as a journey, this relationship develops gradually after establishing trust and an openness to feedback from your coach.

Coaching relationships should be for a proposed period of time. It should be anticipated that the experienced other will equip coachees with the skills to enable their success then release them to grow.

Can you be coached if you don’t display these attitudes? Of course – it just might take you a little longer.

Holistic Education for Diversity and Inclusion as Competitive Advantage for Prosperity

Written by Harold Deigh

Harold Deigh is an Educator and burgeoning Entrepreneur, qualified in International Business & Management / Economic and Social Policy / PGCE PCET (Post-compulsory Education and Training). His education, like most, includes lived experiences and circumstances, differences and intersections and indelible input of our five senses. His training and teaching experience in IGCSE Business, Humanities, Pastoral care, PSHE, SMSC, Citizenship, Health and Social Care and Well-being. Likewise, he is conversant in Value creation, Sustainability, ICT in Global Society (ITGS), Digital and Financial literacy, Global Holistic education, Customer relationship and Customer service.

It is good to know that life is a relationship – a series of shared moments. Moments of gratitude that we have a wonderful world, beautiful people, we belong, we overcome, with joy to enjoy, through the good education of attitude of appreciation and affection, conscious action and outcomes.

Duty and responsibility, like diversity, calls for accountability. We need to educate well and engage more. We learn, yearn and earn for a good quality of life, lifestyle and existence. To survive, manage and cope with our mental, physical, social and cultural, financial, environmental (natural and physical) health and well-being chores. But most importantly, to prevent and protect, safeguard and uphold such fundamental values of shared humanity and care of habitat (between and within countries) and its efficacious notion to serve and be served for prosperity and posterity.

The case for Holistic Education (HolEd) in helping understand Diversity and Inclusion (perhaps as seen in symbiotic nature of Biodiversity or Interdependency or Relationship), is inspiration to support a framework as a guide to better positive decision-making, problem-solving and finding right or good solutions. It employs Sustainable Enterprise, Computational Thinking, Input-Process-Outcome methods, benefits of ICT and Artificial Intelligence (AI), Sustainability Accounting, Social media, News and Information – that ensures carrying out significant but sensible power of responsibility (…that ‘Power is Responsibility and Accountability’). Engaging due diligence and duty of care, with commendable onus to humanity and habitat. We are bonded in our human traits to good quality of Life, Lifestyle, Livelihood, Liberty, Love, and Alive to enjoy the beauty and goodness they bring, and a gratifying, satisfying life of coexistence, well-being and wellness of mind, body and spirit. Recent research – THE POWER OF HOLISTIC EDUCATION – Bold News (boldnewsonline.com) May 30, 2023, highlights this.

Good knowledge of the importance and benefits of diversity and inclusion (especially as a competitive advantage (The Importance Of Diversity And Inclusion For Today’s Companies (forbes.com)– 03/03/2023) is relevant to business bottom line in particular, and society in general. I engage to explore this through the lenses of HolEd. But also embarking on creating and promoting, a comprehensive, and constructive Global Holistic Education Study Programme and Seminars of existing published accredited and approved educational resources and guides of awareness and appreciation of ‘Good and Valued Education’ and ‘A Better Life…a Better World’ pedagogy. This includes better understanding and empowering of HolEd, addressing and raising awareness of contemporary issues, changes and challenges.

Our task is to show and evidence that HolEd is worth exploring in how to proceed to successfully manage Life, Business and Society, including esteem Fundamental British Values (FBV) of: Democracy; Rule of Law; Liberty; Respect and recognition, both tolerated and celebrated, in institutions, individuals and business entities. Otherwise, its discouragement or slow demise is indicative we are against it and thus harbour unhelpful and toxic consequences for many. I particularly treasure the knowledge acquired in PCET as invaluable, especially learning, unlearning and relearning topics on:

- Issues, Policies and Values (IPV)

- Managing the Learning Environment (MLE)

- Supporting and Tutoring Learners(STL)

- Teaching, Learning and Assessment(TLA)

- Emotional Intelligence Leadership

I seek to develop and engage with others, creating an all-round beneficial educational experience of importance, value and worth, with policies, processes and procedures regarding Holistic health, Wealth and Wellness, Nutritious food for our Energy source and sustenance (food for thought!). We thus embrace Fundamental Universal Values, and C21st skills for future prosperity, and good knowledge on survival for sustainable and inclusive successful business and enterprise models. A mantra of ‘No harm, hurt or hate’ to self or others and awareness, appreciation and effective and efficient means to learning, ensuring principled judgements and learning in the philosophy of UBUNTU – “I am because you are”. A conscious relationship has knowledge of good thoughts, intentions, actions and anticipated outcomes.

Physicians are made to “…first, do no Harm” – the Hippocratic oath. Society must emulate further: no harm; no hate; no hurt; no hostility or humiliation. Challenging times and daily chores come and go, so does rampage, anger and rage. As ‘valued educators’ we can courageously and confidently contest and seek to cancel amongst others, the Ills of society, misguided values, bad role models, stereotyping, by addressing and preventing the causes of these. But ensure society is imbued with the indelible disposition to heal, help, capture, cultivate, collaborate, celebrate humanity with co-existence of culture, commUnity, sustainAbility and harmony as we grow to, love and adore, create and appreciate, give and serve, care and share. There is such a thing as society… consciously functioning with humility and hope, to create, produce, sustain value and worth of a beautiful world and wonderful people…the opportunity of presence, acknowledgement and participation of individuals with varying backgrounds and perspectives, embracing our concerted successes from good education, accomplishments and achievements.

Redefining representation in engineering careers

Written by Virtue Igbokwuwe

Virtue Igbokwuwe is a civil engineering graduate from the University of Southampton, currently working at Eurovia. She recently took part in Tomorrow’s Engineers Week - an annual celebration run by EngineeringUK. Her YouTube channel, The Virtuous Life, has over 5,000 subscribers.

Looking back, I can recall the exact moment I heard the words ‘civil engineer’. I was having a conversation with my A-level physics teacher about an essay she had set. She told me about the profession and the wider engineering sector. She opened my eyes to a fascinating new world full of brilliant opportunities. I wouldn’t be where I am today without her advice and guidance. I’ve made it my mission to encourage more girls to follow in my footsteps and hope that you can help. So, I’d like to tell my own personal story of how I became a civil engineer.

Before starting at the University of Southampton, I remember desperately searching ‘civil engineering student’ on Google and YouTube. I was desperately trying to find someone like me studying the course or in the industry. I remember seeing a lot of aspiring Lawyers and Doctors on YouTube but not a lot Engineers, especially Civil Engineers.

Ask anyone what an engineer is, and they will inevitably paint a picture of a middle-aged man with a clipboard wearing a hard hat. Since entering the field, I have learned that the narrative around engineering being male dominated is so outdated. It really couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, my cohort split at university was 60:40, men to women. It’s an aspect of this industry that I wish many more girls thinking of pursuing a career in engineering were aware of.

I decided to take matters into my own hands. I started a YouTube channel, The Virtuous Life. When I began filming videos, I had two things in mind. The first was representation: showing a young, black woman in the field; hoping to inspire people. The second was to change narratives: showing the world that civil engineering isn’t a male-dominated field anymore. I began documenting life as a civil engineering student, including my lectures, labs, site visits and summer placements as a contractor. Today, my channel has more than 5,500 subscribers.

It’s my ‘Day in the life…’ videos which resonate the most with viewers. They are a chance to see the day-to-day activity of a site engineer or a placement student. Not everyone knows an engineer or has one in the family and YouTube vlogs bridge that gap. I have become the ‘neighbourhood engineer’ that people need. It is so important for people to feel like they are represented. Seeing someone like you in a field you wouldn’t expect goes a long way, and people downplay the impact. From my experience, seeing people in a field or position I never imagined was possible inspired and motivated me to pursue a career as a civil engineer.

I receive comments from subscribers about how my YouTube videos have influenced their A-level choices and their desire to pursue engineering. They are a testament to the change in narrative that is so desperately required. We need to make the sector attractive to not only women, but more representative of our wider society.

I believe if we start showcasing inspiring people in the engineering and technology field earlier on in our school years, it will give young people a chance to make a well-informed decision on what career path they want to go into. It’s hard to have an idea of what you want to do if you’ve never seen or heard of the profession before. We have a duty to inspire and guide the younger generation and show them the amazing works that Civil Engineers do, the mega projects and the local ones! There are many organisations that aim to increase the representation of women and ethnic minority in the Engineering industry such as EngineeringUK, the EDI Team at the Royal Academy of Engineers, Girls Under Construction, AFBE-UK and Go Construct. Partnering with such organisations, or getting involved with initiatives such as Tomorrow’s Engineers Week, can allow the message to be reached by more and more young people. It also means that schools can partner with those organisations and hold events, talks or workshops for the students to increase their exposure to the world of civil engineering and the variety of pathways into it.

Graduating with a first-class degree in civil engineering has marked a new, exciting chapter in my life. I will continue to post videos to document life in the industry and hope to continue inspiring the next generation of engineers.

Virtue took part in a live broadcast to mark Tomorrow’s Engineers Week 2023. To watch the recording on-demand and access free curriculum-based resources to inspire young people about future careers in engineering and technology, please visit www.teweek.org.uk

Global Citizenship and the Role of a Global Network in Education

Written by Nadim M Nsouli

Nadim M. Nsouli is Founder, Chairman and CEO of Inspired Education. Founded in 2013, he re-evaluated traditional teaching methods and created a new model for modern education. Today, 80,000 students in 111 Inspired schools across 24 countries benefit from a student-centred approach and globally relevant curriculum.

With digital communication facilitating the exchange of ideas, the world is more interconnected than ever before. As such, it’s increasingly common for individuals to identify as global citizens. This presents opportunities for young people. Yet also poses challenges.

Adapting to globalisation necessitates a strong sense of self-identity and an open mind. Individuals engage with other cultures and challenge stereotypes. Thus, learners must be equipped with the knowledge, skills, and values to navigate and contribute to the world in which they want to live.

There’s a growing recognition that educating for global citizenship is of importance. In 2012, the United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon, said “Education is about more than literacy and numeracy. It is also about citizenry”. Global Citizenship is an all-encompassing concept that acknowledges the web of connections and interdependencies in the world. According to Ban Ki-moon, “Education must fully assume its essential role in helping people to forge more just, peaceful and tolerant societies.”

Students’ desire for international travel and cross-cultural programmes has been apparent for some time. In the past, a one-dimensional approach to this was for an institution to partner with a pre-existing educational facility in the location of interest. However, we’ve witnessed a substantial transformation in the way educational institutions operate, i.e., the emergence and rapid growth of global school networks. With a presence across countries and continents, they’re bringing about a new age of learning possibilities.

Educational institutions are recognising that global citizenship education can develop and enhance much-needed values and skills that will better equip students in a changing world. The concept of ‘global campuses’ has gained prominence, wherein the focus is on cultivating a multicultural ethos.

The Inspired Education Group demonstrates this model with 111 institutions that provide its students with opportunities beyond the capabilities of a single entity. Nadim Nsouli, CEO and Founder, describes it: “We’re now present in 24 countries around the world. This allows 80,000 students from different cultural backgrounds to meet and learn from one another.” Each campus offers a safe space to explore complex and controversial global issues. This approach encourages learning from, and about, people, places, and cultures that are different from our own.

Beneficiaries of the Global Approach to Education

Academic freedom and inquiry are encouraged in international education. It’s a force for promoting open, safe, and peaceful environments. The ability to cultivate global citizenship is grounded in the commitment to giving learners the tools to bring about positive change.

To be effective global citizens, individuals need to be proactive, innovative, and adaptable. They must be able to identify and solve problems, make informed decisions, think critically, articulate persuasively, and work collaboratively.

An educational institution is traditionally centred on imparting knowledge to its students through academia. However, the acquisition of these ‘soft skills’ is also needed to succeed in workplaces and other aspects of 21st-century life. At the crux of fostering global citizenship education – and by association, these skills – is a network.

How a Global Approach Translates to the Classroom

The powerful message of Aesop’s quote “In union there is strength” has never been more relevant than it is today, as educational institutions embrace multiculturalism. Many campuses are now interconnected, which allows students to access any of them – and their specialisms – with ease. This is even more powerful with the addition of extracurricular activities facilitated abroad, providing invaluable experiences. Nadim states: “To develop a rigorous global understanding, an education for global citizenship should also include opportunities for young people to experience local communities. Global campuses, exchange programmes and summer camps offer this.”

Teaching global citizenship itself requires methodologies that facilitate a respectful and empathetic atmosphere. This includes techniques like in-depth discussions and cause and consequence analyses. The objective is to foster critical thinking and encourage learners to explore, develop, and articulate their views while respectfully listening to others. “This is an important step,” says Nadim, “These methods of critical discussion may not be unique, but used in combination with a global perspective, they build understanding and foster skills like critical thinking, questioning, communication, and cooperation.”

Facilitating a participatory classroom environment requires a significant shift in the role of the teacher. They move from being the primary source of knowledge and direction to a facilitator. One which guides as students adapt to think critically, assess evidence, make informed decisions, and work collaboratively with others.

Creating an active classroom environment requires the adoption of a learner-centred approach. This means that the teacher becomes an organiser of knowledge, creating a holistic environment that supports students. As Nadim affirms: “Rather than being passive individuals simply answering questions and competing with their peers, learners must assume an active role. This means taking responsibility for their learning as well as their understanding of the global context of their lives”.

Summary

The notion that all human beings are equal members of the human race is central to the concept of global citizenship. Regrettably, entrenched beliefs in the supposed superiority of certain groups persist in our words, actions, and systems. The educational space is no exception. It can manifest, knowingly or unknowingly, in policies and curricula.

We view the world based on our own culture, values, and experiences. Hence a range of perspectives will exist on any given issue. Thus, gaining a comprehensive understanding of a subject relies on the exploration of other cultures.

As the world grapples with complex problems, global citizenship education has emerged as the gold standard of any institution. This is fuelled by a growing movement promoting peace, human rights, and sustainability. These three pillars are the foundation upon which global citizenship education stands. As Nadim remarks, “The future belongs to young people who can think critically and creatively, collaborating across borders and cultures.”

A Curriculum That Empowers Young People in Care

Written by Anu Roy

Anu is a TeachFirst leadership Alumni and digital trustee and teacher committee lead for charities in England and Scotland. She is currently a digital curriculum development manager and works in inclusive education projects incorporating tech.

This year is the first time I have developed and designed curriculum models for young people in the care system. Although students I have taught in previous roles come from a range of backgrounds, this role is the first time I have looked at curriculum specifically through the lens of an education that often forgets the difficulties faced by care experienced young people.

Out of nearly 12 million children living in England, just over 400,000 are in the social care system at any one time. They face a lot of disruption in their learning journey due to personal circumstances, financial difficulties and challenging home circumstances. This means in comparison to their peers, care experienced young people fall behind in most education and health outcome indicators.

Working with a team of educators, social workers, web developers and UX/UI designers, these are the ways we believe curriculum development can help experienced young people thrive:

- Introduce context alongside technical concepts: technical concepts across all subjects can be difficult for CEYP to master in a short space of time so contextual information wedged on either side of a technical explanation will enable their understanding and grasp to learn and embed the technicality in their wider learning framework.

- Champion peer learning– CEYP could have challenging interactions with direct instruction if it reminds them of unpleasant previous instructor situations therefore activities that use peer learning not only lowers the stakes for them to develop their self confidence and interactivity in a lesson but encourages building friendships within the classroom while learning key concepts together.

- Open ended ethos– instructors and teachers should veer away from specifying the outcome of a learning topic as ‘to achieve grade _’- instead the learning objectives should first be anchored to exploring the curiosity around the topic with prompts such as ‘what would happen if____?’ or ‘what could we learn if we explored how___’. Academic pressure to perform instantly can feel overwhelming for CEYP. While they should not be met with lowered expectations, instead the reframing helps to welcome them to first explore before learning the topic and moving on to an evaluative stage where they gain more agency.

- Knowledge connection outside the classroom-Learning feels more relevant for CEYP when they are introduced to topics through the lens of real world use. Introducing a curriculum through a skills development framework linked to increased employment motivates them to understand the use of each topic, further strengthened by real world examples, work based scenarios and soft skill demonstrations. It helps them bridge the transition from education to active skill application and any learning based curriculum should also have opportunities through project work for practical applications related to public speaking, project management, team building and problem solving for CEYP to gain experience in these areas.

Many educators are unaware of the students in their classrooms who come from a care experienced background. While this should not be the only aspect of their identity to focus on, a student centered approach to relationship building alongside these curriculum findings should enable educators to build strong relationships by understanding the story and journey many of their students have taken to make it to the classroom and learn each day. Aimed with this knowledge and bespoke approach, schools and their wider communities can foster a sense of belonging for care experienced young people, something they have been denied of for too long.

Seeing the Unseen

Written by Tyrone Sinclair

Tyrone is deputy headteacher of Addey & Stanhope School in London. He was a contributor to the BBC Teach resource, Supporting care-experienced children.

A significant majority of educators are drawn to the profession because they aspire to be catalysts for change. However, they are often taken aback by the limitations they encounter as they grapple with the multifaceted aspects of the profession. Change through support is a very delicate skill, one often not covered thoroughly whilst training, but it necessitates intentional leadership at an institutional level. Nonetheless, educators possess a unique liberty in that we are all leaders, regardless of our level of authority. We all possess the capacity to foster safety and facilitate opportunities for change within our respective spheres of influence, whether it be in our classrooms, through the curriculum, parental engagement, meetings, trips, and so forth – the possibilities are endless.

We are currently living in one of the most inclusive eras in human history. Whilst this allows for celebration, it also compels us to delve deeper and consider who is being included. Whose voices are being marginalised? Whose experiences are being disregarded? Who is seen and who is unseen? Ultimately, how is equity being applied in these circumstances?

The fight for inclusivity is a pursuit of social justice that extends far beyond the confines of the classroom. Its effects can be recognised and rewarded on a global scale. Although we may be making progress towards inclusive equity, it is important to acknowledge that not all spaces prioritise safety or consideration for all individuals. Education, therefore, is an embodiment of social justice as it endeavours to address the various inequalities that exist within society by creating opportunities and explicitly striving to provide equal opportunities for all.

This raises the question – what can I, as an educator, do? Amidst the external pressures, deadlines, targets, and ever-expanding job description, how can I make a meaningful change?

I believe the answer lies not in what can be done, but rather in how it can be done. I have been challenging educators to reconsider the spaces they create for safety. I urge them to contemplate the most vulnerable student who may ever enter their classrooms. Consider all the safeguarding concerns, whether they are rooted in familial or contextual factors. Reflect on the experiences these students have endured not only throughout their short lives, but even on that very morning. Contemplate the sacrifices and who they have to leave at the door just so they can walk into your space and conform.

Care-experienced young people are often among the most vulnerable individuals we encounter. The range of experiences they may have endured is vast, but more often than not, these experiences are far from ideal. Imagine the worst possible scenario. Consider the impact this must have on their worldview and how this trauma manifests itself in their thoughts, pathology, behaviours, and even their physical wellbeing. Now, take into account the intersectionalities that these young people may identify with. How much more challenging would it be for those from marginalised groups? How would you connect with such a young person? How would you welcome them into your space? What measures would you put in place to support, encourage, reassure, and protect them? How would you guide them if things went awry? Undoubtedly, your approach would be thoughtful, compassionate, and considerate. We know that for every vulnerable young person we are aware of and deem worthy of intervention, there are countless others who remain unknown and unsupported. Moreover, the strain on resources and support services makes it even more arduous for marginalised groups to access the help they need. Thus, your approach and support as an educator are pivotal to the safety and wellbeing of these young people, as your intervention may be the only kind they receive. Consequently, every interaction becomes an opportunity for intervention.

The experience of marginalised groups is to be unseen. This is often unintentional, but it is undeniably systemic and institutionalised. As educators, we are on the frontlines, and it is our duty to intentionally see what the world chooses to ignore. We must consciously consider worldviews and experiences that may differ fundamentally from our own. We must be intentional about change.

What can care-experienced young people teach us?

Acknowledging the unseen requires us to not only consider young people who have experienced care, but also challenges us to broaden our considerations even before they enter the system. Many care-experienced young people were once students in someone’s classroom, often unseen and unnoticed. However, we have the privilege of seeing the unseen and deliberately choosing to create safety for them within the spaces we control and have influence over.

For more information about the BBC Teach resource, Supporting care-experienced children, please visit https://tinyurl.com/ywykzd5h

Peanut Brittle or Marshmallow? (Growing into Flexible Working)

Written by Erin Skelton

Erin is first and foremost an educator and her extensive experience includes a diverse range of roles, encompassing both pastoral and academic leadership positions, across both independent and state education settings. Prior to joining Bright Field, Erin’s most recent role was as Assistant Head and Head of Sixth Form in a top independent girls' school. In this role, she nurtured her students, instilled a sense of purpose and provided invaluable mentoring to prepare them for life as a woman in the 21st century and beyond.

It’s 8:39 on a Monday morning as I sit and type this. I’ve already had breakfast, fed the dog, emptied the dishwasher, folded and put away the laundry, and undertaken the mammoth task of ensuring that my son was prepared for the day and is sitting on the school bus. My first meeting isn’t until 10:00… Normally, with military precision I would be up, packed and gone by 7am on the dot to get myself to school for 7:45. Logged on, armed with the first of many caffeinated drinks, I would already have sent multiple emails and dealt with numerous issues before anyone else arrived; after all, I had spent the last seven years as Assistant Head in charge of a large Sixth Form in a top independent school.

And yet, here I am, on a Monday morning, sitting in my home office. I am one of many senior leaders in education who have opted out of senior leadership. If you’re reading this, then I’m sure that you have read the constant stream of headlines and statistics about teachers at all levels wanting to redefine what their working lives look like. Well, I am one of those people.

Full disclosure, the decision to step out of a SLT position has been a challenging one. As an Assistant Head, on a good day, I felt like I was making a significant difference to the school and students; I felt a real sense of purpose, like I was an empathetic superhero. That is a feeling I still love and it’s one of my core values. But realistically, I knew that to achieve that I was working sixteen-hour days, I was at every school event, answering emails at 11:00pm before I closed my eyes, and the first thing I would do in the morning was to check my email with dread to see what had come into my inbox whilst I was sleeping. I was sacrificing my time, my family and ultimately my wellbeing, and I was measuring my sense of worth solely by my job. But what about the holidays, I hear you say. Most Heads of Sixth Form work most of school holidays; we field university and UCAS application issues, worries about mock and real examinations, we prepare for and support Y11 students around GCSEs and entry to our Sixth Forms and we work tirelessly around A level results, university admissions and UCAS clearing. Almost every issue that lands with us is a matter that could change the course of a young person’s life. It is not a job for the faint of heart.

I spent so much of my time giving inspirational assemblies and talks about knowing your worth, being brave and following your dreams, that I had ultimately known for several years, that I needed to do that for myself, even if I knew that I would probably have to unravel many of my own self-beliefs to get there. I loved my role and I love my school. I was also fully aware that I could have tried to find a better balance, that I could have had healthier boundaries around my job, but the nature of my role meant that if I did that, it would be the students who lost out, because my role wasn’t about ticking boxes, it was about people and what made me a great Head of Sixth Form was that I was invested in ensuring every student was happy and as successful as possible.

Cue discussion about being authentic and following my dreams… The reality was that I felt trapped; I had been a teacher for eighteen years, all of which had been in some type of leadership position. I had no idea what it was to not have leadership responsibilities and like so many of my colleagues, I thought the only thing that I could do was “teach”; we forget the vast skill sets that teachers have. I made lists, I sounded people out, I listened to podcasts, and I read. I tried to remember what my dreams actually were.

Eight months ago, armed with my thinking, I walked into my Head’s office after psyching myself up for three months to speak to her. That initial conversation with my Head set things in motion, and I returned to my school in September as a part-time main-scale teacher for the first time in eighteen years. Here’s what I’ve learned so far…

We are educationalists not simply teachers. We have a vast skill set and are not defined by the parameters of a job description. Teaching seeps out of our pores and when you work outside of one singular educational setting you get a real sense of how this is a superpower that can be applied in so many areas of life and work.

I didn’t step down, but I did step out. I think it’s important to think about the language that we use when we talk about changes in the ways people work. I have had such mixed responses to my decision. When a person wishes to work more flexibly, particularly when the decision has nothing to do with childcare needs or health, that decision is often questioned on the grounds of their ability to “cope”. We shouldn’t have to cope; there are no awards for giving so much of yourself into any role that you have nothing left. I am a highly successful, highly competent leader in education; I didn’t fail because I wanted to step out of the parameters that were defined for me, I wanted to draw my own.

Flexible working doesn’t come without its challenges. I work full-time across two roles: one teaching and one largely within educational settings both in the UK and globally, plus some additional passion projects. Balancing the demands of both roles requires a lot of organisation and commitment to both institutions equally. I would add that as teachers, we are very institutionalised; our days run to a formulaic schedule, and we become adept at putting ourselves last during the course of the school day. This is a real issue for everyone I have met who has moved to part-time teaching or moved out of the classroom altogether. Suddenly there isn’t a bell telling us when we can go to the toilet, a timetable dictating how we spend our days, or a salary that we receive irrespective of the additional hours we put in. Suddenly we have to navigate part-time working conditions, changes to the complexity of how our tax, pension and benefits are calculated and sometimes a lack of understanding from the full-time staff managing our HR and payroll.

Stepping out of a leadership role and remaining in my school has also personally been a real challenge for me. I now know that I could have undertaken my SLT role part-time as well as taking on my new role with relative ease. I am also slowly settling into being a classroom teacher where there are no expectations for me outside of that role. It is hard to have to say ‘no’ when students approach me for support, or you can see colleagues struggling with the burden of their workload or a problem they would have previously approached me to solve, particularly given the nature and size of my previous role. At present, there is still a lot that I am doing behind the scenes to support which I am not paid to do, but I do so because I care, and my decision has had a significant impact on the school.

If you can make peace with the frustrations, flexible working can give you space, time, and a balance to your perspective and the way you live your life. It’s very early days for me, but already I am excited about utilising my skills in new ways, taking the time to meet new people, read inspiring books and work more creatively on projects that have a wider impact. I am noticing little things, taking reflection time, being out of doors, being more present with my family, resuming old hobbies and taking up new ones.

I find myself growing to fill an expansive space and I welcome it.

Make Yourself Heard

Written by Bennie Kara

Founder of Diverse Educators

Public speaking is a fact of life in the teaching profession. We speak to students all the time in classrooms, but every so often, we are called to deliver assemblies, or to deliver training to staff, or to speak to governors. Some of us are supremely confident in talking in front of students, but shudder at the thought of talking to a group of adults. If you’ve ever felt a sense of dread when you are asked to stand up and deliver spoken content outside of the classroom, you’re not alone. According to the British Council, 75% of us suffer from anxiety about talking in front of a crowd.

Speaking in front of the crowd may tap into a range of fears. We might fear being nervous and how that might affect our assignment. We might fear judgement, or fear that we won’t get everything across that we want to say. We might fear that people won’t listen. We might fear forgetting what we are saying in the moment, stumbling, freezing, feeling embarrassed. These are valid fears and affect most of us.

Whose voices are valued in the public space? Some people are less confident in their speaking abilities because their voices have been silenced. In the UK, global majority teachers work in a predominantly white British teaching workforce; we know the statistics on the ethnic make-up of leadership teams in education. Global majority teachers may suffer from the voicelessness that is part and parcel of existing in marginalised groups. This isn’t just true in terms of race and ethnicity; it is also true for sexuality, gender, disability, and neurodiversity.

Voicelessness erodes confidence. So it is hugely important that we learn how to find a voice in the public space and to feel like we belong there.

Finding your message

Regardless of the occasion, it is important to define the message. Speaking in a staff meeting, delivering a talk to parents – what is it that we want to get across? Not just in terms of the information, but also about you. How are you defining your leadership in the moment through what you say and how you say it?

The message might be small, or it might be momentous. In either case, we need to find ways to define a sense of who we are as engaging speakers and to ensure that we can convey our message effectively. This takes thought, planning, and crucially, constructive practice.

The best public speakers have elements in common. One of the most powerful tools in public speaking is your ability to tell a story. Storytelling is vital in public speaking, in the appropriate contexts. An assembly without a story, a keynote without anecdote can feel dry and impersonal. The most skilled public speakers I have encountered know how to weave a story into the talk with a deftness and ease that seems intuitive.

But storytelling is not intuitive for all. Some people are completely comfortable in selecting anecdotes, examples, stories, tiny useful narratives for the public engagement. Others have to think more carefully, but that careful process can lead to brilliant, engaging public speaking.

The Diverse Educators ‘Make Yourself Heard’ Course

Designing this course, for us, means that we can support you in developing the right mindset for public speaking and provide you with practical strategies to make yourself heard. It aims to develop a voice with you in small groups so that you have the chance to listen, learn, practise and hear feedback.

If you would like support in developing your voice, join us on the ‘Making Yourself Heard’ course using the details below:

Monday 15th January and Monday 11th March 4-5pm

Part 1 – Monday 15th January 2024 4.00-5.00pm

The first session is an intensive look at how you can plan, develop and deliver talk in public so that you can create impactful messages.

Part 2 – Monday 11th March 2024 4.00-5.00pm

This second session aims to support you in considering how to speak impactfully in public. It will cover planning, rehearsal and delivery style in a safe, supportive space with fellow educators.

Nb/ Both sessions will be held on zoom, they will be recorded so purchasing the recording is also an option if you are unable to make either of the dates.

The sea belongs to me again: Steering my disabled body through an able-bodied world

Written by Matthew Savage

Former international school Principal, proud father of two transgender adult children, Associate Consultant with LSC Education, and founder of #themonalisaeffect.

On a coaching call recently, my dog, Luna, and I were surprised by a sudden knocking at our front door. I apologised to my coachee, grabbed my crutches and went to investigate. Our house is at the remotest edge of a small crofting township on the Isle of Skye, in north west Scotland, and so doorstep visitors are extremely rare. Usually, Luna alerts us when anyone appears even on the horizon, but her guard was clearly down, and the knocking made us both jump.

We moved to Skye in the summer of 2021, post-lockdowns and having recently returned to the UK after a decade working in the international schools sector, our two children soon to fly our family nest. Like so many itinerant educators, enriching and mind-opening though the experience had definitely been, we were determined to find roots, and this was, we hoped, to be our ‘forever home’.

It offered a remoteness that appealed strongly to my inner introvert, and with nature at its absolute grandest at our finger- and toetips, I would be able to do some of the things I loved the most, every single day, hiking, trailrunning or losing myself in Luna-exhausting walks. In fact, there was a footpath from the end of our drive, snaking across the moors to a colony of harbour seals, but one jewel on a rugged coastline I longed to explore from the rocks, a kayak, or even, if I could brave the temperature, the waters themselves.

However, the weekend before our move, I began to fall ill. A complex neurological disorder would, within just a few months, confine me to a wheelchair, completely unable to walk. Swapping two legs for four wheels, my life would change unrecognisably. Two years on, try as I might and despite the ‘disability pride’ badge occupying pride of place below my computer monitor, I am struggling to be proud of my disability, even though – with each passing day, week, month – the lines between my disability and me are disappearing completely.

Many of my everyday symptoms – the allodynia that secretly burns my skin, the angry twitches that shock my muscles, the stammer that silently benights my speech, the spasticity which tugs my shrinking legs – are invisible to others. But everyone can see that I cannot walk, and learning to navigate an able-bodied world with a disabled body has taught me so much. About our bodies and all the things we take for granted; about a world designed and built by and for those who can walk; and about the power perpetuated by that design and construction, the tyranny of physical space.

I am privileged to be engaged in a project, with tp bennett architects and in association with ECIS, in which we aim directly to challenge that power and to seek what we are calling ‘liberated school spaces’. Teams of educators, architects and students will explore how the different spaces in our schools – circulation, classroom, sustenance, personal and outdoor – can too easily exclude, marginalise and oppress the very, marginalised groups they should most seek to include. A school campus, like the world beyond its gates, is, in so many ways, an instrument of power, and that has to change.

But it is beyond the school gates that I have most experienced this tyranny myself, and I share here some small windows into my story. These snippets are about planes, trains and automobiles; about bathrooms, doors, and bathroom doors; and about curb cuts, actual and metaphorical. Because all of these have, in their own way, kept me on the margins of society; because I know that my ‘protected’ characteristic is unprotected, tyrannised even; and because each of these spaces could, and should, be liberated.

Beyond the safe and known confines of our Highlands bungalow, I navigate any internal or external space in my electric wheelchair. The ‘door’ is a convenient metaphor for the portal to any community of power (we talk about getting our ‘foot in the door’, for example); but that portal, for me, is literal. If I want to enter or exit any building, or room therein, I am typically faced with a heavy, handled, hinged, outward-opening door, despite the fact that the only door that is easy and safe to open in a wheelchair is a sliding door, manual or, better still, mechanised.

This challenge is everywhere, in many an ‘accessible’ hotel bedroom, and especially so when I want to enter an ‘accessible’ bathroom. Almost every time I have wanted to use a public bathroom, I have had to ask a stranger if they would open it for me. As someone who does not believe students should have to ask for permission to use the bathroom, I certainly do not think I should have to do so myself. To add insult to injury, many an accessible bathroom does not provide sufficient turning space either; and flying out of one airport recently, I was told there was no accessible bathroom available at all.

As a consequence, I commonly try to minimise my fluid intake when out of my house, so that I do not have to suffer the indignity of a bathroom whose ‘accessibility’ is but a mirage, a performative badge that may tick boxes but does not liberate the disabled user. This is not to mention the bizarre requirement in many a public space that a wheelchair user report to a cashier in a nearby shop to collect, and return, the special bathroom key. I recognise this is to ensure able-bodied users do not occupy this targeted space – but, again, the design, much as it may seek to liberate, does anything but.

Whilst I love the success with which Zoom masks my disability, I love my face-to-face work. Norah Bateson calls this aphanipoiesis, the communing and commingling of multiple stories in a submerged, liminal space from which could eventually emerge a seedling of hope. And for me, professionally, nothing compares to this; how fortunate am I that the pandemic lifted its pall such that I can safely travel around the world again. And yet each flight, or succession thereof, treads on my agency and dignity, and my comfort and safety, at every juncture.

The system through which one requests special assistance when booking a flight varies between airlines in all but one thing: its complexity. Even airlines which build it into the booking process rarely pass this information on to the check-in staff, leaving me having to explain my medical condition and requirements again, all in earshot of an increasing, and increasingly irritated queue. And most airlines require persistent and repeated phonecalls and emails to secure a promise only that they will endeavour to provide said assistance.

I used to rely on the airport wheelchairs, but the understaffing of the privatised assistance teams, combined with the fact that most airport wheelchairs are not self-propelling, left me, too often, stranded in a corner, facing a wall, without access to food, water or a bathroom for several hours. Therefore, I invested in a foldable, electric wheelchair, which is now, to all intents and purposes, my legs. Just as I manage, despite numerous objections, to take it to the plane door, I am always promised that it will be returned to the door on landing; but, on landing, I am commonly told that it has been “lost”, panic setting in until it is discovered again, somewhere in the baggage hall.

Going through security is, at best, undignified and, at worst, invasive; on only one occasion have I been permitted to take my wheelchair onboard, and so my agency is taken away with it; boarding is a spectacle, whether or not I manage to avoid being forcibly strapped into the onboard wheelchair; the safety instructions, written or spoken, never mention someone like me; my crutches are routinely confiscated, and retrieving them, should I need the (inaccessible) bathroom, is laboursome.

And, on landing, it is not uncommon for me to remain on board for up to an hour after everyone else has disembarked, the crew for the following flight patiently caring for me until assistance has arrived. Every flight I take takes away a little part of me, and I am lesser forever thereafter. And yet, with intentionality, consultation and compassion, air travel is a space that could easily be liberated. The likes of Sophie Morgan fight this fight on my behalf; I used to give feedback myself, but nothing ever changed, and it is hard then not to give up on feedback altogether.

I love curb cuts. Designed in California by Ed Roberts and others in the 1950s and 1960s, they took one of the discriminating spikes of hostile architecture, and literally excised it to create a ramp that directly benefits people like me, but from which everyone else also benefits. Such a powerful idea is this that I use its metaphorical equivalent as one of the instruments of equity and justice through which every aspect of the school experience can be adapted for universal belonging.

However, whenever I navigate the pavements of a city, I have learned not to depend upon the existence of the actual curb cuts which would enable me to move, unencumbered, through those built environments. The only city where I have not faced this difficulty was Amsterdam, but this is because of the prevalence, far further up the food chain, of the bicycle; the wheelchair was an afterthought. I often talk to schools about the tussle, in any practice, between coincidence and consistency, and this is, fundamentally, an equity issue. The same is true for the humble curb cut.

In London recently, I selected a restaurant based on its social media and website having declared it fully accessible, only to arrive and find there was a step to enter the premises. This is not just frustrating; it is humiliating, distressing, and infuriating. The step may as well be a brick wall. Then there is the construction work which has temporarily diverted pedestrians on to the road, but without a ramp to cut that curb. And on a recent train journey, a step-free station was closed, which meant I had to ask several strangers to lift me, on my wheelchair, from the train at the next station.

Which brings me to the ramps, installed or designed with the best intentions, deliberate acts of inclusion, whose gradient is simply too steep to carry my wheelchair safely upwards. On at least three occasions this year, it is only the sharpest reflexes of a group of adults coincidentally nearby that prevented my wheelchair tipping backwards and sending me tumbling to likely serious injury below. Or the promised ramps which, for whatever reason, did not materialise, leaving me depending, again, on others, this time to lift me up the steps to the upper level.

I share none of these stories, any more than I would the myriad other stories I kept back, to elicit pity. No disabled person I know wants that. I only aim to offer a window into the tyranny, intentional or otherwise, of the able-bodied over those whose body is disabled, but one example of the power exerted by physical spaces over those for whom said power is but a pipe dream.

Too often, the burden of fighting for accessibility, equity and justice falls to those on the margins. Some schools I visit thank me for shedding a light on the inaccessibility of their campus; it is not uncommon for a school to ask a queer educator (or student) to educate the school on the harm of a cis-/hetero-normative curriculum, culture and climate; and many a school will finally seek to adapt to the needs of the minoritized only when an educator or student happens to inhabit that particular minority. And yet, as my own story epitomises, disability is a characteristic that could suddenly strike any one of us, temporarily or permanently, at any point of our life.

Consequently, I have had no choice but to adapt myself and my life to a world which has not, nor will it, adapt to me. The crutches offered to me, by default, collapsing bruisingly beneath my faceward-falling body too many times, I commissioned bespoke crutches which not only could bear my full weight but also came with attachments for mud, sand and even snow. And I invested in a disability-adapted, fully recumbent, motorised trike, on which I can now explore the lanes and byways of rural Skye, without depending upon anybody else.

Meanwhile, let us return to our unexpected visitor, knocking to the surprise of Luna and me in the midst of my coaching call. He was part of a team, funded by the charity, Paths for All, who were rendering fully wheelchair-accessible the entire footpath from the end of our drive to the rocky shore in the distance. And he wanted to inspect my trike, to make sure that the sharpest bend in the new path could accommodate its particular turning cycle.

I may cry easily these days, but I was moved to tears by this gesture. The view from my front room, until now teasing me with a landscape that I could only watch and imagine, was soon to be liberated. Both natural and built environment were bending to my needs, and the power was shifting. Very soon, I would be able to cycle to the sea, for the first time since we moved here. The seals may not have missed me, but I have certainly missed them; and, in this space, for the first time, I would finally feel free. I have yet to manage kayaking, and I cannot swim any more, but still, in a small but significant way, the sea belongs to me again.