The Absence of Diversity in the Literature Curriculum – and its Lasting Impact

Written by Anjum Peerbacos

20 years experience as a teacher

Riz Ahmed made a powerful speech regarding diversity in the Arts: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/riz-ahmed-warns-parliament-that-lack-of-diversity-in-tv-leads-people-to-isis-a7610861.html Riz Ahmed warns Parliament that a lack of diversity in TV is leading people to Isis www.independent.co.uk

He stated that if young people could not see themselves as part of the narrative or the mainstream representation, they would turn elsewhere to feel that they had a sense of belonging. He said it was the responsibility of the Arts to reflect society; to reflect the patchwork that makes up a wider world, and our global community.

In so many ways, Literature is another Art form and should be doing the same. When we study texts in class, there should be an opportunity for students to be able to see themselves in the literature world. However currently that is not the case.

For more than two academic years now, I have taught the new GCSE curriculum for English Literature, I have taught ‘Lord of the Flies’ by William Golding, ‘An Inspector Calls’ by J.B Priestly, ‘A Christmas Carol’ By Charles Dickens, ‘The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ by R.L Stevenson, and ‘Romeo and Juliet’, by William Shakespeare. White males that are no longer with us, have written all of these texts.

It may be that because I work in a boys school that these texts have been chosen, as the demographic of the school is largely white and male; however one could argue that in such circumstances it is vital that we expose our young people to the width, and breadth of the spectrum of the society in which we live. Students regardless of demographic and gender should be exposed to a range of writers’ experiences and Literature. It broadens their horizons, and ultimately their experiences. Students have studied the above texts, in addition to a small collection of poems largely about war, with the anecdotal inclusion of Benjamin Zephaniah and John Agard. ‘The Conflict Cluster’ largely addresses the atrocities of war, and as a result these young people have not been exposed to the wealth of Literature that exists in the world.

Across the exam boards, the choices have been extremely narrow. There are few women and even fewer texts from a diverse or BAME background. I appreciate the need to study the works of Shakespeare but, not counting The Bard, on the AQA specification there are 19 opportunities to explore other Literature texts and only 2 are from non-White authors.

On the Edexcel specification there are 15 opportunities to study a text written by a white male, there is only 1 non-White BAME author. On the Edexcel specification, all White Male playwrights write the Modern Drama Texts. WJEC offers two options which are non-White authors, however is more inclusive of female writers over time.

Obviously, I understand that we want children to study, learn and love Shakespeare and he is a white male and is from the 17th century. There is one re-occurring BAME author for modern prose and that is Meera Syal and her novel ‘Anita and Me’, and I can’t help wondering how much of a token of her appearance on the curriculum is.

My other concern regarding the curriculum is does it need to be British? And is there a place for Modern World Literature or modern world prose or drama? Why are we limiting our young people to English British largely male Literature, which is no longer representative of the global world in which we all live?

In addition, what constitutes British Literature? Is Syal considered English Literature or British Literature? Moreover, why are we not considering the likes of Malorie Blackman? Blackman is a modern Black female author and is much needed. She addresses many sensitive issues within her texts which provide the debate needed, which would also meet the Social Moral Spiritual and Cultural (SMSC) criteria, which Ofsted demands of schools.

I happen to work in a boys school, and I am teaching an entirely male curriculum, bar a few poems in the poetry anthology, and my worry is that these boys are going to live, work, learn and prosper and flourish in a world which includes men and women. A world, which includes the young and the old. A diverse world which includes people from all walks of life. So why is our Literature curriculum not reflecting this and preparing them for the alternative view? For the different perspective? For the obscure or the distance or the far-reaching? Why is it so inward looking and insular? Surely, this is then a potential breeding ground to consider anything different as ‘The Other’? How is this progressive?

As Ahmed stated the Arts should be a representation of the world and narrative in which one can see oneself. Why aren’t ‘we telling these kids they can be heroes in our stories, that they are valued’? Ahmed goes on even further to state that if a young person cannot see themselves in the wider narrative then ‘we are in danger of losing people to extremism’. I think he makes some valid points. If you are studying a text for six weeks in a classroom, and potentially over five years you do not find yourself represented in any of those stories, then is Ahmed making a wider point? Do we not have a responsibility to deliver a narrative which is outward looking and less insular?

The curriculum was developed under Michael Gove, https://qualifications.pearson.com/en/qualifications/edexcel-gcses/english-language-2015.html

and I feel as though he has been able to dictate a curriculum, which he saw fit in an era, which is no longer fitting or applicable to our young people now.

The issue has been raised before, however I feel that now more when students are asked to regurgitate texts in exams, texts that they may not be able to relate to, or even understand, it has become a more pertinent issue. In light of recent events where we have witnessed a rise in hate- crime, communities feeling isolated and marginalised, immigrants being targeted; I think that now more than ever our young people should understand a wider broader spectrum of literature appreciating and celebrating difference and diversity. Of course, there is a place for Shakespeare and Romantic poetry, and of course, there should be an appreciation of the likes of Dickens and Austen. However, should there not be an opportunity to experience World Literature?

Our young people are interacting on a global platform and developing a global community. If I were a young person living in 21st century Britain, I would not think the Literature that I am exposed to on the current curriculum is in any way reflective of me, or the world in which we all live.

Why Diverse Representation Matters in Children’s Books

Written by Orla McKeating

Entrepreneur, coach and motivational speaker

I started Still I Rise Diversity Story Telling for Kids in 2019 as a passion project as I really didn’t see enough representation in kids’ books. As a single mother of a bi-racial child I had learnt the importance of this for the well-being, influence and mental health of this for children, but I didn’t imagine the impact this would have on so many young people around the world. Still I Rise is now a global business, lockdown forced us to do virtual storytelling sessions which has massively built our community and the feedback we have received from parents, psychologists, teachers and the kids themselves has been incredible. And having worked with hundreds of children globally we can see the impact first-hand of the importance of diverse and inclusive books, how it builds confidence, empathy skills, how it inspires and creates impact and allows for deeper connections with society as a whole.

I was blissfully unaware of the importance of a diverse and inclusive world having been brought up in largely white Northern Ireland into a family of privilege and shielded from the Troubles we experienced until I was in my late teens. I lived in Belgium for 10 years post university in a culturally rich and very international society and moved back to Belfast in 2012 where I began to bring up my son as a single parent. We always read books together from when he was so tiny, and I wondered was it really that great to read from such a young age? But now at 7 years old, he is such an avid reader and communicator and I can see that it absolutely did. What I did notice was that there were so few characters in the books that looked like him. This baffled me and I wondered why this was. Of course, I could find the books when I looked for them, but they weren’t so readily available as they are now. Why is this representation so important though I hear you ponder …?

Well. The whole world is not white, able bodied and with a nuclear family structure. When children read books and don’t see people like them in them, they don’t feel included in society which can have a massive effect on their own confidence and self-worth. However, when there are characters similar to themselves culturally or ethnically, I have seen it reinforce a more positive view on themselves and pushes them towards goals and allows them to believe that anything is possible! How can you be what you can’t see, right?

Seeing characters, ideas and experiences in books that are unlike ours allows our children to open their minds and teaches them (and us for that matter) to value the whole human race and not just people who look like us. This equity within literature teaches empathy from a young age which helps them build secure and strong relationships with those around them while promoting tolerance and acceptance.

Being included in books and seeing other people like them facing challenges and making a difference in the world really helps kids have a deeper understanding of our world and how great things are possible. It creates impact, allows them to have role models they may never have met who influence their actions and behaviour, help them to overcome challenges and push them to their full potential.

Books with a diverse and inclusive representation allow a mirror or a window for what our next generation can do for themselves. They read about a wide range of human experience – familiar or strange, real or imagined and they can manifest a larger window of opportunity for themselves. This allows for authentic connections which allows them to feel less alone, more important and increases self-esteem.

While embracing books within education that promote diversity, equity and inclusion it is also important to encourage our kids to see colour, culture, history, identity and acknowledge the impact it has on our lives and experiences. Encouraging an actively diverse life through books, TV, films, toys, food music and embracing curiosity, welcoming questions and having the conversations can really encourage the next generation to have a clear understanding and acceptance that every human deserves to be treated fairly and with respect no matter who they are. And imagine the possibilities in a world like that.

We Need Diverse Books

Written by Anna Szpakowska

Professional Development Lead at Lyfta

The outpouring of shock, disgust and despair surrounding the murder of George Floyd this year rightly drew our attention to the discrimination suffered by so many on a daily basis. It also drew our attention to the institutional racism pervasive in much of our society. This heightened social awareness led to discussions of diversity in education, with calls for the history curriculum to include black British history and many English teachers sharing their recommended diverse reading lists or schemes of work online. In fact, some young people started a petition to ask the government to include The Good Immigrant and Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race on the GCSE English Literature specification.

It was heartening to see so many educators impassioned to provide an education to young people which directly tackled issues of discrimination; it’s wonderful to work for a profession that not only wants to provide young people with knowledge and skills but also wants to make the world a better and more just place.

This is not the first time something like this has happened. In fact, in 2019, Edexcel were forced to add more texts from black, Asian and other minority ethnic writers to their GCSE Literature specification, after complaints about there being ‘too many dead white men’ on the reading list. This decision whilst perhaps well-intentioned, was met with disappointment from educators suggesting that the choices of texts, added by Edexcel, were not challenging enough. And, as Diane Leedham pointed out ‘As with all the exam boards in 2014, it’s clear that the people choosing the set texts that they frame as ‘diverse’ don’t have much knowledge of diaspora literature’.

Nevertheless, according to statistics from 2019, only 12.6% of students sitting an English Literature GCSE in 2019, sat the Edexcel qualification. In fact, the largest percentage (85%) of pupils sitting an English Literature GCSE in 2019 sat the AQA qualification. And figures from the AQA Examiner’s Report in 2019 show that of the most popular texts studied by all centres completing the AQA English Literature GCSE, all of the authors were white men, very few of the characters were women and none of the characters were black or Asian. The dilemma for educators then, is not only are the exam boards not providing enough suitable texts to truly reflect the experiences of most of us in society, but that the majority of schools themselves continue to choose to teach texts written by dead white men.

As teachers of English literature, we are the gatekeepers of books and literature accessed by many young people. It is, therefore, our moral obligation to expose young people to a wide variety of texts that provide them with a range of experiences, voices and characters. As Botelho and Rudman explain (expanding on Sims-Bishop’s metaphor of windows, mirrors and doors):

‘Children need to see themselves reflected so as to affirm who they and their communities are. They also require windows through which they may view a variety of differences…. Literature can become a conduit- a door- to engage in social practices that function for social justice’

Where are all the women?

For the purposes of this post, I will focus my thoughts on female writers, characters and issues of sexism and misogyny. That is not to say that I place more value on the inclusion of female writers and characters than I do on black authors and characters, gay authors and characters or authors and characters with disabilities, for example. I just feel that as a woman, I am best placed to discuss the issue of women in literature.

So, why then, in 2020, do we have to have a discussion about young people accessing texts written by and about women? And, why is it so important anyway? Aren’t women equal after all? Unfortunately, the answer is a resounding no. Despite the equal pay act being introduced fifty years ago this year, the UK’s gender pay gap is still 17.3% with the World Economic Forum reporting that it will take 202 years to close this gap. As well as this, statistics gathered from 2019, show that the number of women and girls murdered in 2019 rose by 10% on the previous year, to take it to the highest figure since 2006. It’s clear there’s much more work to be done before we can claim our equality.

With no shortage of female authors writing about the female experience, why do we continue to choose to teach texts written by and about men? The myth of the superiority of the ‘great’ English literary canon has a lot to answer for but what worries me a great deal is that teachers continue to buy into this myth. By continuing to teach these texts – and more often than not, attempting to mirror the GCSE curriculum at Key Stage 3 too – we perpetuate the notion that one voice (the white male) is superior to everyone else’s.

And, yes, it’s true that children may be reading plenty of texts by women and about women in their own time. But, when they haven’t been taught the critical skills to unpick the sometimes-sexist depiction of female characters, I fear that we are at risk of inculcating a generation of young people with sexist ideals.

Both young women and young men need to see a variety of female characters. They need to be able to discuss issues of sexism. It’s not our job to police what they read and discourage them from reading books such Louise Rennison’s Angus Thongs and Full Frontal Snogging because, as Kimberley Reynolds explains it depicts female characters who are ‘only interested in friends, fashion and fun’. But it is our job to show young people alternatives and teach them to read critically. Characters like Starr in Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give, for example show a passionate, intelligent, strong and socially responsible young woman. Or, Dana in Octavia Butler’s Kindred could provide opportunity for discussions of gender and race whilst also providing them with an insight into the Antebellum South and the science fiction genre too. For teenagers (some of whom will already be sexually active), it’s important to address the issue of sexual assault. Books like Amber Smith’s The Way I Used to Be could be helpful in achieving this.

What’s key here is that teachers clearly have the passion, the willingness and the desire to teach a wider variety of authors and texts. I hope the passion and impetus we have garnered this year does not disappear and our calls for a more diverse reading list can be implemented. But what must also accompany these reading lists and all literacy education is critical discussions about how and why characters are presented in certain ways.

Thoughts and Musings on... Diversity

Written by Audrey Pantelis

Audrey Pantelis is an associate coach, consultant and trainer. She is a former Headteacher of a Special Educational Needs and Disabilities school and a current Diversity, Equity and Inclusion consultant and leadership coach.

What does diversity mean to you? What about cultural diversity? Often mentioned, usually at interviews where the interview panel will want you to know that you “know” about diversity. I would put diversity in the same bag as equality and equal opportunities. When I was a teacher, these words scared me. Not because I didn’t know what they meant, but because I couldn’t be sure that I was applying them to my delivery of the subjects that I was teaching. As I reflect on those early years, I know that I loved promoting difference – probably because as a black woman in a predominantly white world, I embraced difference. I have always loved any aspect of character that shows individuality in any shape or form and it may also answer why I love special educational needs pupils. I was a mainstream teacher before changing phase to SEND in 2008. I guess I thrive on the fact that despite difficulties, we can express our true selves; our true characters. Overcoming our difficulties is a strength and shows true resilience which is a value that I so admire. And we can bring this to any table we choose to come to.

I spoke at the last DiverseEd conference in Slough in January 2020 with @HeadsUp4HT and had really enjoyed the set up and the drive that came from meeting likeminded colleagues. There were a lot of groups and grass roots movements that I had not heard of before but there was something compelling about their missions and values that resonated with me. I came away from the conference pumped up and wondering how I could get more involved.

When lockdown took hold of our lives and all face-to-face meetings were on hold – I was informed me that DiverseEd would be a virtual event and asked if I would look at ‘Smashing Ceilings’. You may have heard of the ‘glass ceiling’ concept – defined as : “an unacknowledged barrier to advancement in a profession, especially affecting women and members of minorities” . From my lens, I would go so far as to say that as black women in the work place we often have ‘concrete ceilings’ to contend with. The main difference being that at least you can SEE through glass and aspire for more – with concrete – that’s it!! This has been my experience. I have been let down, as we all are as we aspire to leadership positions, but for me it’s been very difficult to work out whether I was the wrong fit, or just plain wrong. When you add ethnicity into the mix – we could be here for a while, trying to work it out.

Cultural diversity is a form of appreciating the differences in individuals. The differences can be based on gender, age, sex, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and social status. Schools have realized the value in acquiring a diverse workforce but what is not so well promoted or encouraged is the opportunity to rise and in turn, steer the culture to embrace ALL. The stereotyping and prejudices, if unchallenged, contribute to a culture that can promote sameness and prevent the celebration of skills, abilities, and experiences.

My fellow speakers: Naomi Ward @naomi7444, Patrick Ottley-O’Connor @ottleyoconnor spoke of their approaches in how we can establish culture (see clip below). Hannah Jepson @Hannahjep also spoke in the same session (Session 3)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Q7RWmbKONo

with me during Saturday’s virtual conference – #DiverseEd on Culture and Diversity – about Unconscious Bias: Recruitment and it really chimed with my own thoughts about how and why we recruit who we recruit. As a former Head of School, I was extensively involved in recruitment and always ensured that I fully considered candidates that weren’t anything like me – as Hannah stated “fit is important” – but it need not mean that I discounted potential employees that weren’t as I wanted. Like a jigsaw puzzle, we may have different shapes, but when we are placed together to make the bigger picture, no one worries about individual shapes, ONLY the bigger picture.

I believe that there is a lack of:

- comfortable, trusted strategic relationships

- positive strategic feedback

- opportunities to showcase breadth of skills and experience

If we don’t increase the amount of black and minority ethnic voices seen and heard at leadership and strategic levels, then how do we expect things to change? How do we smash those ceilings, glass or otherwise? Change means being uncomfortable – and the challenge doesn’t need to be aggressive but there needs to be clarity in the outcome with a plan and milestones to ensure that we are on the way to achieving that plan.

I am a big believer in action and we all have agency to make things happen. We are privileged in that respect – all of us. I’ve currently got the same excitement and passion bubbling up that I felt after the DiverseEd conference in January 2020. What I am aware of, in these post #BlackLivesMatters post #Covid-19 days, is that this is a REAL opportunity for change. A chance to do things differently. For too long we have said that same things and nothing has changed. We need allies, we need authenticity, we need curriculum reviews, we need visible leadership, we need programmes that enable our up-and-coming talent to remain in education and be the leaders of tomorrow, not become disillusioned as they are under-represented or oppressed again and again! We need the systems that already exist to be challenged to enable that change to take place. Yes – the conversations will be uncomfortable – but no one needs to get hurt! Let us LEARN from one another.

And….. my biggest take away from my session and indeed the conference itself, is that I would welcome a genuine level playing field. Merit is the only currency that we should be utilising to enable us to progress. Remember – “its difficult to be what you cannot see”.

I have focused on diversity from my own lens but the beauty of #DiversityEd conferences is the inclusion of LGBT, disability, gender, allyship viewpoints, as well as ethnic minorities. It’s such an important conversation – and in the current climate we MUST keep talking; and turning our words into actions. #MyDiversityEdPledge is: to use my voice to lead from where I am and to support others so that they can challenge their understanding of diversity and Black perspectives. What’s yours?

“It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognise, accept and celebrate those differences”.

Audre Lorde

Black Lives Matter: Then, Now & Always

Written by Wayne Reid

Professional Officer & Social Worker

The murder of George Floyd is the latest in a long line of atrocities and brutalities endured by the global Black community. This has a long history. Longer than is sometimes convenient for honest acknowledgement. I notice some commentators are referring to George’s ‘death’, which is a dilution of what occurred. George was brutally murdered by a Police Officer and the world has seen the evidence.

The context to George’s murder is emotive and cumulative: the Amy Cooper ‘race grenade’; endless examples of police brutality cases in the US and UK; modern-day systems of oppression and the historic and ongoing the suppression of the effects of slavery and colonialism in mainstream education. These factors can accumulate and create an acute sense of anger and rage. These emotions can manifest into civil disorder and criminality. It has been evidenced that anarchic extremists are infiltrating protests to covertly fuel acts of looting and violence, which is then reported by the media in such ways to discredit the protesters. This detracts from the causal factors that have triggered the protests – and if we want to discuss looting, how about the longstanding looting of Africa’s natural resources?

As a Black British male social worker, I write this article on Black Lives Matter ‘wearing numerous hats’, as this issue affects me deeply both personally and professionally. Clearly, my opinion cannot and should not be understood as representing all Black and ethnic minority people/practitioners. We are not a homogenous group. It was important to me for my employer, the British Association of Social Workers (BASW), to publish our organisational position statements before I wrote this article, as I refuse to be the tokenistic ‘Black voice’ of BASW. I’m one of many Black voices in social work. It is my reality, that my role enables me to be heard more broadly than others.

I’m immensely proud of the authenticity and candour of BASW’s statements responding to George’s murder and in support of the fight against racialised discrimination.

Those who follow me on Twitter, or who are on my mailing list, will have observed my campaign to educate, empower and equip Black and ethnic minority people – and importantly our allies – with various information and resources.

On occasions, I have been outspoken about the delayed/weak position statements and responses from prominent social work leaders and organisations. Given that social work’s core values and ethics are deep-rooted in anti-oppressive practice and social justice, this eventuality has been particularly disappointing for me and many others within the profession. Sadly, these values and ethics appear sometimes to have been taken for granted, diluted or ignored in recent years/decades. Perhaps austerity has desensitised us? Overall, I’m sure Black and ethnic minority social workers and service-users will welcome the late (if weak) acknowledgements and platitudes from some of the social work elite. The statements will send a necessary message to employers and other stakeholders across the profession about the relevance of current world events to social work policy, practice and education. However, I think some of the statements could be strengthened by providing a clearer commitment to systemic reforms to eradicate all forms of racism through specific, measurable, achievable and realistic targets.

During the furore surrounding George’s murder, some individuals/organisations have recoiled at the suggestion they may be racist. “I’m not a racist!” is the common response. The accusations seemingly worse than the facts. I would argue that racism is not an absolute mindset, instead it’s a rather fluid one. There are degrees of racism. I imagine very few people reading this article would identify with extreme right-wing neo-Nazi racism, but many will have stereotypical views about certain ethnic groups which they project in everyday situations (if they are honest/self-aware). There is a structural and lazy acceptance, that ‘lower level’ prejudice and oppression are somehow separate – with the former being considered a less important issue. However, I believe if this changed it would engender a real decrease in the overt, violent forms of ‘race-related hate’.

In my view, the spectrums of white privilege and white supremacy are also broad – not absolute. This graphic here best describes my views. Fundamentally, there are a range of behaviours and oppressive systems that are socially acceptable, which we must address and redress to tackle racism effectively in all its ugly manifestations. For example, the statement ‘all lives matter’ is covert racism, as it ignores the history and current circumstances of Black people globally. Physical colonisation and slavery may no longer be acceptable or legal, but colonisation and slavery of the mind has been the norm since their abolition. Black lives matter applies then, now and always.

The recent misdemeanours of Dominic Cummings show us there are clear double standards; not just from a class perspective (which was perpetuated by the media) – but also through the lens of white privilege. I wonder how Raheem Sterling would have been portrayed flouting the lockdown rules.

Labels/terms such as Commonwealth, ‘hostile environment’, and ‘BAME’ need to be re-examined. BAME does not describe who I am. BAME is a clumsy, cluttered and incoherent acronym that is opportune for categorising people of colour as a homogenous group – when we quite clearly are not. Of course, I cannot speak for all people of colour. I understand that ‘BAME’ can be operationally helpful when exploring the overarching effects of all things racist. However, it misses so much nuance and subtlety, that it can be seized upon by those who wish to deny racism as a white problem. Routinely, I hear people comfortably stating that BAME people “can’t even agree amongst themselves”. This sloppy reductivism, leads to terms being invented such as ‘Black and Black’ crime. I have not heard about “White on White” crime – ever.

Some quarters consider having a small minority of people from Black and ethnic minority groups who reach positions of power (including within the current Cabinet), as progress, in and of itself. I respectfully disagree and would go so far as to say it is actually unhelpful in this case. I think a contingent of these people only seem to identify as being people of colour when it is expedient. Often, they have championed policies that in fact would have previously disadvantaged their own families – which is basically ‘pulling up the drawbridge’ and ‘morally bankrupt’. In some ways it is worse than having a ‘conventional racist’ at the helm. To quote Malcolm X: “I have more respect for a [person] who lets me know where [they stand], even if [they are] wrong, than the one who comes up like an angel and is nothing but a devil.” Politician’s have form for allowing their personal ambitions to override ethics and morality. Their denials can play beautifully into the hands of those who seek to maintain the existing order. As black and ethnic minority representation is disproportionately very low, these people do not necessarily use their power for good and structural inequalities remain unchanged.

At this current juncture in race relations, there has been much discussion about how ‘white allies’ can be ‘anti-racist’ and supportive to the cause. Of course, allies can be personal and/or professional. So, what is really behind those awkward smiles and sugary sympathy? Actions most definitely speak louder than words. It’s time for all well-intentioned platitudes and recycled rhetoric to be converted into meaningful activism and ‘root and branch’ reform. This weblink will provide allies with relevant resources on their journey.

‘Blackout Day’, on 07/07/20, is when Black and ethnic minority people (and their allies) will not spend any money (or if they must, only at Black businesses). This is so important, as it sends a strong message to the capitalist elite in the only language they understand – money. See this video for more information on ‘Blackout Day’. We must build on this impetus and momentum to be taken seriously.

It is imperative that social workers evaluate their roles and (moral and regulatory) responsibilities. Current race relations require social workers to be proactive and do our homework to stay contemporarily astute as allies to Black and ethnic minority colleagues and service-users. There are various opportunities through BASW to develop your expertise in this area with our Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Group, events, branch meetings and training programmes. Also, I will be leading a Black & Ethnic Professionals Symposium (BPS) for BASW members in the coming weeks, so do contact me at wayne.reid@basw.co.uk or @wayne_reid79 – if this is of interest.

We all know that organisations are at times avoidant of these issues, but as social workers we must recognise that silence on racism is complicity with the oppressors. BASW will not remain silent on this issue and we implore you to do the same.

‘One world, one race… the human race!’

Don't Tuck in Your Labels

Written by Bennie Kara

Founder of Diverse Educators

Written January 7, 2018.

I am the woman that always has a clothes label sticking out somewhere. In any given day, some kindly person will reach behind me and tuck it in. And I, without fail, will apologise for that label and the fact that someone had to decide what to do with me.

You see, clothes labels are really useful things. They tell you what to do with the item. How to take care of it – how to fix the item if it is damaged in some way. It stays there as a reminder that the item needs to be nurtured. Lots of us become irritated by them – how many times have we cut the label out because we can’t forget it is there – perhaps it’s rubbing against our skin, making us feel uncomfortable. I do it all the time with the vain hope that people will not have to fix me up and make me presentable.

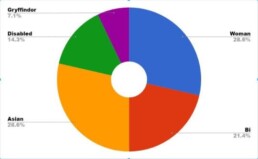

I have made many jokes over the years at various conference about winning the competition on how many labels I have. We categorise people in so many different ways and I have seen it as a laughing matter. So when I was thinking about my labels, I decided to create a pie chart of the make up of me. Mostly just in case my Maths teacher is watching – my Maths GCSE started with 30 mins of me panicking because I had forgotten how to draw a pie chart.

So if you want to see what my clothes label says – this is me.

It took a long time to decide how much of me I could allocate to the different labels. I am a woman. Quite considerably so, according the number here. I am also equally Asian. It gets harder when I have to decide just how much of me is on the LBGT spectrum. I define as bisexual and have been in a relationship with a woman for a long time. All of these categories I have become comfortable with – while I know they present me with challenges, I have spent my life getting to know them.

I have come to know myself as a Gryffindor too. This is not in jest. I will not have anyone disagree. I’ve taken the test.

It is my last label that is more recent and perhaps the one I struggle with the most. I learned not long ago that I have hearing loss in both ears and it is more pronounced in my left ear. I will be wearing a hearing aid soon to help me function in loud spaces, to help me understand what people are saying when I can’t see their faces.

I mean, I know I’m a woman and can’t lift heavy things or be in charge of a boardroom. I know that I am Asian and therefore should probably be teaching Science and not English. I know that I am bisexual and this means I am greedy/just not willing to admit I am gay.

But I was not prepared to be disabled, albeit in a small way. In some ways I have to confront here my own misgivings about having a hearing impairment in a profession that is built on listening to children in order to teach them. I sat in a car park and cried. Because this female, Asian, bi person didn’t want another label – especially one that could literally mean people think I cannot do my job. How many glass ceilings for me?

It has taken time to adjust to it. It chafed. I could feel it rubbing. But I have left it there because it gives people another way to know me.

Some people will say: if we take away all labels, we can just be people. I absolutely agree. I want to be able to teach without any of those. At the risk of sounding like a below the line Daily Mail commentator, stop going on about your labels – it creates the victim complex. It’s not important to the way you teach, so just shut up and get on with it. Identity politics creates resentment. I resent you and your labels.

I don’t think any of us walk around with our labels on our sleeves. If teaching is a profession in which your authentic self is required for children and adults alike to connect and know you, if it a profession in which people are the centre then I do not want to lie, either overtly or by omission.

The average 18-44 year old lies twice a day. I am sure that you are sitting there thinking – well that’s low. I can smash that statistic by 9am in the morning on any given school day. But the lies I tell because I have to are now starting to grate.

There are things I can’t say, choose not to say, places I won’t ever visit with my partner – and it is exhausting making all of those decisions about who I can be when I am simultaneously juggling the demands of the curriculum, behaviour, marking, meetings, paperwork. Wouldn’t it just be easier for me and more real for the students if I didn’t have to think about my pronouns so carefully? Or worry about who is going to see me with my partner in the local area?

I spoke recently about the curriculum and how having diverse voices delivering content doesn’t take away from what we teach our students – when we teach the Ramayana or about Malian women’s contributions to local industry, we are not saying do not teach about Wordsworth or Dickens. Perhaps as a female, Asian, bisexual, disabled Gryffindor, I can enrich rather than detract. Hiring me, allowing me to be free within a role, means a better education. Not because I am better. But because I can bring my knowledge and still teach yours really quite well. There is enough oxygen for all of our stories, told with pride. Authenticity in teachers allows students to understand humanity in all of its guises. We actively prevent learning when we lie, when we omit.

I have seen this quotation many times and it occurs to me that I no longer see it as being about other people. I see it as being about myself and about all of us that walk in different shoes. My silence about about me is collusion. I am colluding with the oppressor. It is unjust that I should be quiet, tuck in my labels to make everyone else feel comfortable, staff, students, parents alike. In remaining silent and not celebrating or sharing all of me as I am, I am complicit.

How can any of these things happen when we are silent?

I am not asking anyone to stand up and shout from the rooftops about their sexuality, disability, gender or heritage. But I am asking you to stand, metaphorically speaking. And speak about your truths without fear. And perhaps, when you feel brave enough because you have a room full of people willing to support you – to act, in the way that makes you feel that you are authentic.

So, if you see me again and my labels are sticking out. Maybe don’t tuck them in.

Closing keynote: Diverse Educators Conference, 6th January 2018